The hybrid tree that conquered the world

The world’s cities have always been radically hostile environments for trees – but there’s one variety that’s proved to be remarkably resilient.

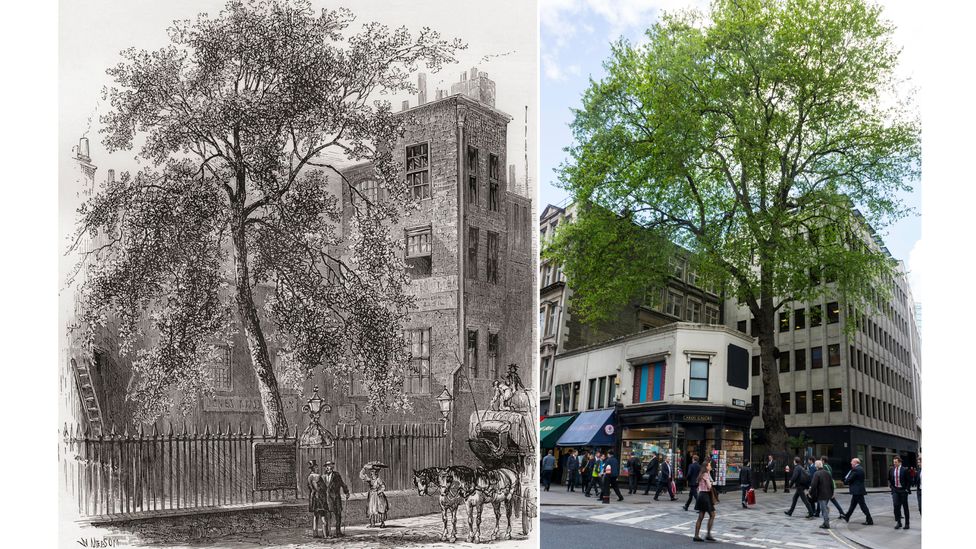

In an unremarkable corner of London’s Cheapside district, tucked away behind black wrought-iron fencing, is one of the city’s oldest residents. With a towering frame and slightly stooped posture, capped with a broad thatch of leathery, star-shaped leaves, this venerable giant is thought to have presided over the city since at least the 18th Century.

Over its lifetime, the Cheapside tree has lived through countless dramas and innovations – slowly inching its way upwards while stonemasons toiled away erecting early coffee houses and banks, then gradually broadening its shoulders as the first electric hackney carriages rolled along the streets below, and later, shading the cars that replaced them. It’s been a stoic witness to the infamous cholera outbreak of 1854 – which led to the introduction of modern sanitation – the 1918 flu pandemic, and the horrors of the Blitz.

But life for this Londoner has not been easy. Hemmed in on one side by buildings and the other by a road, it inhabits one of the most polluted parts of the city. And like most urban trees, when it rains it’s either inundated with runoff or left thirsty. Its roots are squashed into heavily compacted, alkaline soil – with little space to stretch out their tendrils without bumping into concrete. The City of London may be an urban jungle, but it’s hardly an idyllic environment for a tree.ADVERTISEMENT

In fact, there’s emerging evidence that urban trees share many of the burdens of other city residents – often living in cramped conditions, riddled with infectious diseases, and suffering from chronic stress. In this unnatural setting, they tend to live fast and die young – research has found that they have mortality rates nearly twice as high as those in rural areas, with fewer surviving trees every year.

“Street trees are typically not getting older than 30 to 40 years,” says Cecil Konijnendijk, professor of urban forestry at the University of British Columbia in Canada. As we speak, he’s surveying the health of the trees he can see from his hotel room during a visit to Brussels. “I can see already in a line of six trees one or two that don’t look healthy,” he says.

The Cheapside London plane tree has barely changed for hundreds of years (Credit: Alamy)

Though it can be easy to think of them as little more than city furniture, urban trees are very much alive – and their struggle to survive is only becoming more extreme. Without a radical rethink of the living conditions of this long-overlooked community, some experts are concerned that our cities could soon lose much of their greenery altogether.

How have some trees survived in these dystopian environments for so long? And what can be done to save the others?

A secret tryst

It all started in the 17th Century. As global trade took off between Western countries and their colonies, among the endless crates of imported spices, silks, ancient artifacts and tea were millions of tiny guests – seeds. Explorers and merchants sent these tiny souvenirs back from wherever they traveled – so as the map expanded, so did the plants available in Britain. Soon English gardens were transformed into showrooms for the flora in the furthest reaches of the planet.

It was around this time that the London plane tree came into being. To this day, its origins remain a mystery. But somehow, amid the chaotic meeting of the so-called New World and the Old, two plants from continents thousands of miles apart – an American sycamore and an Oriental plane – met and reproduced.

One possibility is that the two strangers may have coexisted on the grounds of the Oxford Botanical Garden, where one botanical thing led to another. An alternative theory is that they hooked up in Spain, where their offspring was first described. Either way, the result was a large, strikingly beautiful tree with a fast growth rate and an unusually robust constitution, able to survive in one of the harshest environments on Earth – human cities. It didn’t take long for the London plane to be a hit.

Within a century these noble plants could be found scattered across London. The exact age of the Cheapside tree is hotly disputed – some say it belongs to this first generation, making it up to 300 years old, while the City of London asserts that it was planted in 1820 at a cost of sixpence.

For regular trees, these early additions are still just youngsters. But for city trees, they’re positively ancient.

Gingko trees have barely changed since they first appeared on the planet 200 million years ago – but they happen to make remarkably good city residents (Credit: Getty Images)

In the 19th Century, London plane trees were used to transform the city’s layout, turning previously naked streets into familiar leafy boulevards – inspired by the same trend in Paris. (One particularly broad specimen in London’s Mayfair, dating back to the Victorian era, was valued at £750,000 by tree officers from the local authority in 2008.)

Even as the harsh living conditions of the Industrial Revolution began to take hold, London plane trees continued to cling on where others got sick. In addition to being unusually hardy, the hybrid giants had some quirky features that helped them adjust to city life, such as the ability to slough off the outer layers of their smog-coated trunks to reveal a fresh patchwork of green and white bark beneath.

By the 1920s, the London plane represented 60% of their city namesake’s trees, and their almost-cartoonishly straight trunks and fluffy crowns had become a regular fixture in many other urban centres around the globe, from Sydney to New York City. They were soon joined a handful of other species, such as the common lime (also known as the linden tree), which currently makes up 45% of the canopy in the Finnish capital Helsinki.

21ST CENTURY GARDENING

From working with contaminated city soil to reconsidering weeds, pests and even lawns, gardening is changing as we adapt it to the realities of modern life. This series takes a look at its future in the 21st Century – and explores how it can be updated to fit with modern sensibilities and challenges, such as environmental awareness and pollution.

An unappealing prospect

Today the London plane is not as dominant as it once was – or quite as robust. Research in the Czech Republic has found that the trees’ health has been steadily deteriorating, and in any given year, the proportion of sickly individuals can be up to 97.5%. It’s widely accepted that when trees are stressed out by their local environment – such as warming cities or life in a concrete street box – they become particularly susceptible to a range of diseases. And this variety has been catching a new kind of fungal infection that causes characteristic sores, or “cankers” on the trunk.

Even for the long-suffering London plane, the conditions in modern cities are a step too far.

While other city trees’ bark used to get choked up with smog, London plane trees simply sloughed theirs off (Credit: Getty Images)

“One of the greatest challenges [for trees in city environments] is just space,” says Andy Hirons, a senior lecturer in Arboriculture at Myerscough College in Lancashire, pointing out that large trees in the wild have vast root structures, often sprawling out nearly as far as their branches do. But in cities, the spaces we carve out for them are “often woefully inadequate for the size of the tree and the ambition those planting the tree have for it”, he says.

These confined conditions then lead to other issues, such as localised droughts – a common problem, as a tree’s roots can quickly mop up the water in its little pocket of land. “A tree with a smaller working environment will cause it to dry out much quicker, so they’ll experience drought cycles,” says Hirons. “And, you know, if a tree is always living on the edge of that sort of stress, they become more vulnerable to pathogens, pests, etc, just like us.”

Not only are city trees imprisoned in small slivers of soil, the soil itself is the equivalent of junk food – without the acidic organic matter that would usually cover the forest floor, the root environment tends to be alkaline, hindering their ability to absorb nutrients.

Even the soil’s structure is all wrong: where there should be pockets of air, the soil is compacted into dense clumps. “This means that it’s physically much more difficult for the roots to grow through and expand,” says Hirons. Eventually this limits their distribution and scale, further limiting their underground world.

Then there’s the pollution. This is ubiquitous – in the soil, there are heavy metals, as well as salt from the de-icing of roads and chemical contaminants from building materials. In the air, particulates block up microscopic pores in city trees’ leaves and smother delicate structures on the surface of the trunk – which plays a surprisingly important role in gas exchange and photosynthesis – while nitrogen oxides are absorbed by the leaves, leading to potentially toxic accumulations.

Finally, there’s the trees’ human neighbours.

Cities tend to trap more heat than the surrounding countryside, forming “heat islands” – so the best city trees can withstand high temperatutes (Credit: Getty Images)

“There are big problems with the ways we interact with trees,” says Hirons. He lists off some common crimes humans commit against their woody bystanders – resting bikes on them, using their protective enclosures as litter bins, encouraging pets to urinate all over their trunks, which alters the ground chemistry. Perhaps most bizarrely, some people even train their dogs to bite living branches. “[It’s] just crazy. Once that bark is lost, it’s devastating for the tree – it’s like losing your skin,” he says.

Crucially, many of the oldest urban trees will have spent the majority of their lives in conditions that were significantly less desperate. While in human terms the invention of tarmac in 1902 may seem like the distant past, for a three-century-old tree the era of these impermeable surfaces – which allow precious water to flow off into drainage channels rather than percolating down into the ground where it can be accessed – is relatively new.

“Effectively what you’re doing [with hard street coverings like tarmac and paving] is decoupling the climate, in terms of precipitation, from the experience of the tree,” says Hirons. Today city trees in some of the wettest parts of the planet are effectively inhabiting miniature deserts. They’re also suffocating.

“Impermeable surfaces really reduce the gas exchange between the root system and the atmosphere as well,” says Hirons. Just like humans, trees need to breathe – they must be able to absorb oxygen through their roots in order to release the energy from their food.

“They had much, much better rooting environments [in the past] in many ways,” says Hirons, who explains that 200 years ago pavements were wider and trees weren’t competing with fibre optic broadband cables for space. “And it’s difficult to see how that’s going to be pulled back.”

In short, just because old trees have made it this far, there’s no guarantee they’ll survive another century.

Many of London’s oldest street trees were planted centuries ago, before the invention of the things that can make their lives difficult today – like tarmac (Credit: Alamy).

A tricky brief

Enter the next generation of city trees, which experts are struggling to recruit.

One challenge is the new awareness of the importance of biodiversity, both for its ecological benefits and as an insurance against new diseases or pests that could wipe out whole species. When Dutch elm disease swept around the globe in the 1960s and 70s, it killed off around 25 million trees in Britain alone. By 1976, the United States had already lost around 38 million trees – few survived.

All this means that city planners can no longer rely on an elite pool of high-performing trees, such as the London plane. Instead, they’re on the lookout for a more varied supply which can thrive in the increasingly harsh conditions urban forests have to offer. And it hasn’t been easy.

According to one estimate, there are currently around 800,000 street trees in London, with the ones that end up on pavements carefully selected by developers and city arborists. But even once they’ve identified a species that could work, getting hold of enough of these trees to populate a city is a huge challenge. There’s often little incentive for plant nurseries to invest the time and money it takes to grow young trees unless they know there’s going to be a market for them in 10 years’ time – and at the moment, most demand is for a narrow selection of small trees like silver birches.

“Frankly, just sticking in really small rowans or birches is not really going to deliver what we want in the future,” says Hirons. “You take away those last statuesque plane trees, and that’s what you’re left with.”

OUR GREEN PLANET

For more stories about plant life and the role it plays on our planet, please visit Our Green Planet, a digital initiative from BBC Earth in association with The Moondance Foundation. It aims to raise awareness of the beauty and fragility of our planet’s green ecosystems, forging a deeper understanding of the important role that plants play in biodiversity.

Next there’s the surprisingly high mortality rate for young trees, which are particularly vulnerable in the years it takes for them to establish in their new home. Hirons says this is currently around 13% – but in some situations it’s significantly higher. Nearly 50% of the new trees added to one street in Toronto, Canada were dead within three years.

However, Hirons is optimistic that cities can solve these problems.

One important change will be to make it clear to growers that there is demand for certain larger tree species, in advance of when they’re needed. But even more vital is designing the spaces they will inhabit with their physiological requirements in mind – ideally, larger pockets of land where they can develop healthy root systems.

Trees whose roots are smothered by hard surfaces like concrete, tarmac or paving slabs can be chronically stressed (Credit: Getty Images)

And support in their early years is also crucial. “It’s like with human children – if you don’t have a good start, you will get the consequences later in your life,” says Konijnendijk. “It means we need to help them along the way, basically.” This includes things like “mulching” – adding organic matter to the root surface to seal in moisture – watering, and making sure they’ve got enough space, above and below ground.

If urban planners get it right, over the next few decades cities across the globe may soon break away from the monoculture aesthetic that London plane trees have lent them for centuries – and pioneer something more colourful. Hirons is rooting, quite literally, for more gingkos (ancient trees that once lived alongside dinosaurs) which are currently popular in Japan.

“I do like gingkos,” says Hirons. “I think they’ve got a lot of character they become sort of more and more on unweildy and wild as they get older. They’re really resilient, and they also can deliver just fantastic yellow-gold autumn colour as well.” Of course, what he’d really like to see are baobabs – strange, bulbous trees that flourish in the Sahel region of Africa on the edge of the Sahara desert – “but then we really would be in the realm of serious climate change…” he says.

—

Zaria Gorvett is a senior journalist for BBC Future and tweets @ZariaGorvett