In his final work, Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees, British nature writer and activist Roger Deakin overlooks the River Wye in western England and considers the influence of woodland ecology on the life history of a river. He reminds readers of the life-giving “vintage rot” of decaying trees, which while still in their healthy middle age will have dead branches, dropped or not, and as age advances, hollows expanding within their trunks. He closes his chapter with a visit to a churchyard where he squeezes inside the hollow of a 1,000-year-old yew tree, looking up into the illumined and illuminating “lantern of its twisted trunk”. The tree was nonetheless in full foliage, blackbirds feasting on its berries.

I recalled Deakin’s enchanting passage as I noticed the ubiquitous signs of “vintage rot” all around me. It began while brushing my teeth one morning. My gaze through the window was level with the excavated knothole on a slender oak tree. Out popped a Carolina chickadee. My most beloved cavity dweller! “Cavity” is not a word with positive associations (particularly while brushing one’s teeth), but cavities, when in trees, are very good indeed. A few days later, over my morning coffee, I observed from our kitchen window a pair of squirrels — mouths stuffed with leaves — using both the front and back doors of their nest hidden within this white oak:

The Bufflehead diving ducks that arrive on our part of the James River around the end of November nest in cavities. So do the Wood ducks I’ve been lucky enough just twice to see high in a tree, seeking a suitable nest site near water. Prothonotary Warblers, Bluebirds, Woodpeckers, Tree Swallows, Purple Martins, Screech Owls and Barred Owls . . . All cavity-nesters.

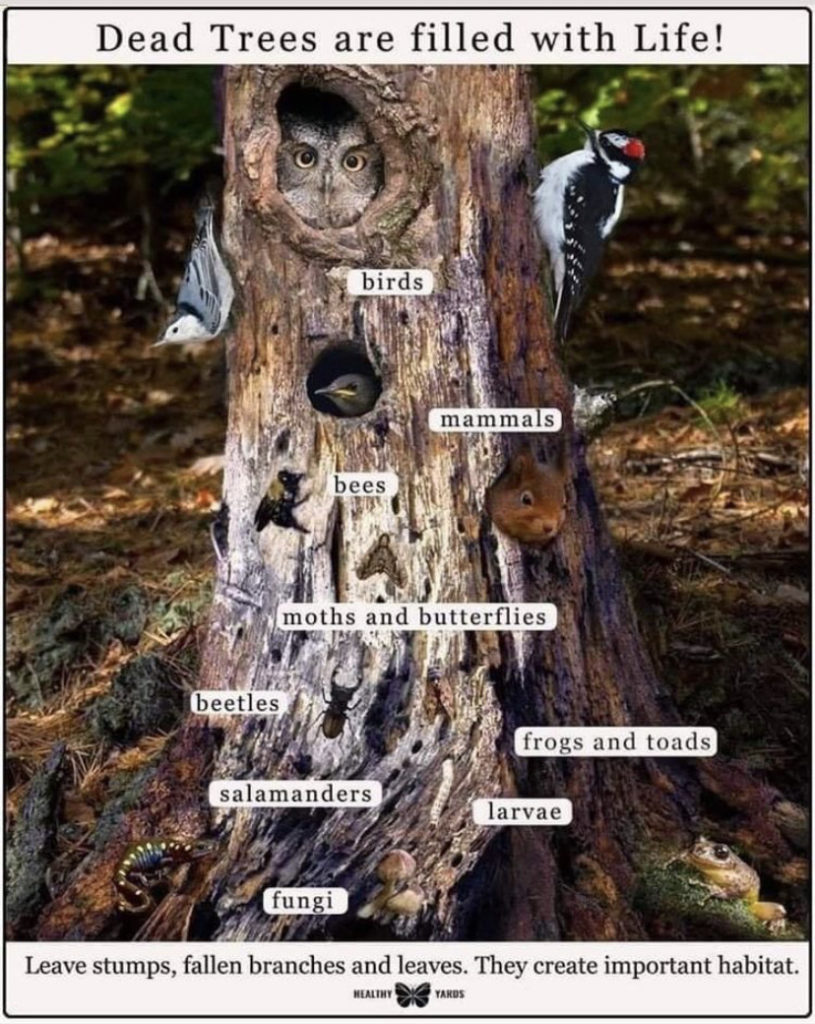

A few months ago, arborist and Urban Forest Dweller contributor Aidan Stewart made “The Case for Keeping Your Backyard Habitat Standing”. It included this illustrative graphic that bears repeating:

A tree cavity doesn’t have to house mammals or birds to provide habitat. The decomposers that feast on the decaying wood are themselves food, and insects and insect larvae found in rotting wood (and leaf litter, my other favorite decomposing organic matter!) are essential to the survival of hatchling songbirds. Or a cavity might be the perfect water catchment system.

Some trees invite curious investigation and show no signs of weakness despite sizable hollows in their trunks.

In the opening chapter of her 1975 Pulitzer Prize winner Pilgrim at Tinker Creek–lived and written near Roanoke — Annie Dillard proclaims, “I am no scientist. I explore the neighborhood.” She finds that, as with everything “nibbled and nibbling”, “we the living are . . . pitted and scarred and broken through a frayed and beautiful land.” Just as we do, trees age, sustain damage, sustain life, carry on. Explore your neighborhood. You will not find a 1,000-year-old yew, but you will find a tree that is a doorway.